AI and the future of writing instruction

How AI exposes the fragile state of writing instruction and what to do about it

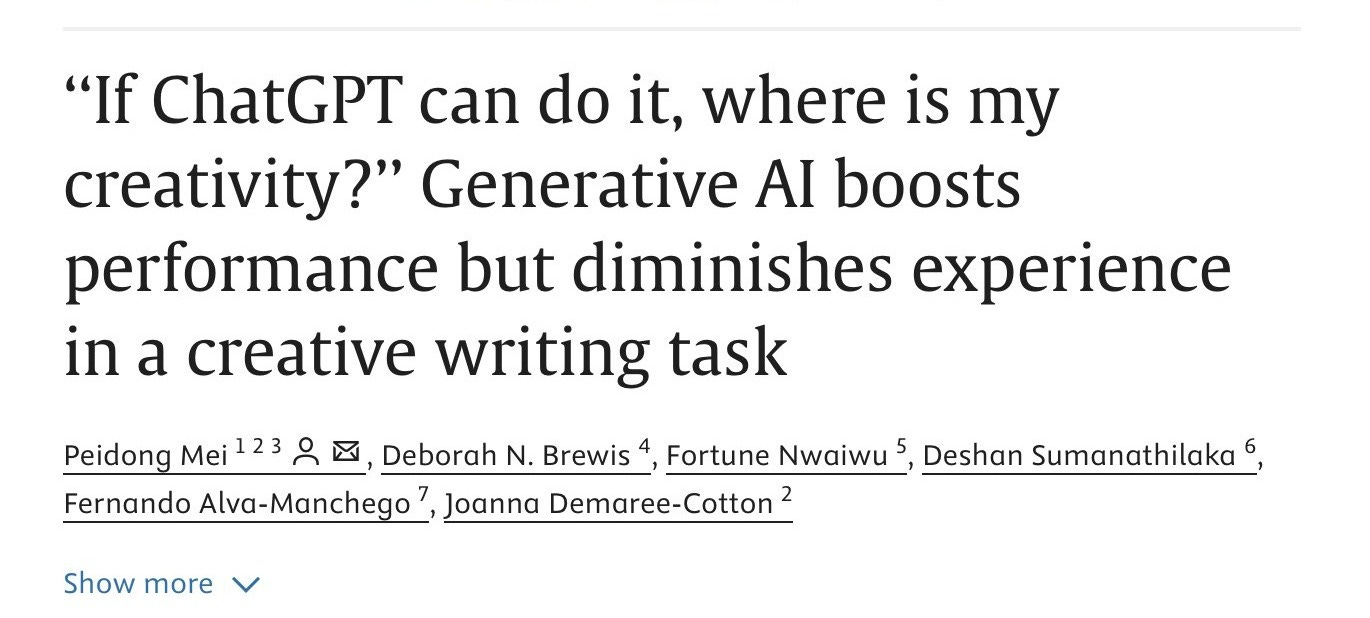

“Although ChatGPT has made tasks like creative writing easier and less effortful, our findings support concerns about the potential devaluation and diminished enjoyment of the creative process” (Mei et al., 2025, p. 10).

Confirming what many suspected, a recent study in higher education revealed that while ChatGPT improved the quality and creativity of students’ writing, their perceived enjoyment and sense of creativity in the process declined. The study found that the cognitive offloading that occurs when relying on AI to do the heavy lifting made the process feel less effortful, but also less meaningful. Though unsurprising, the report prompted a brief ludditical unease about the future of writing instruction with the rise of AI and LLMs. After some reflection, I’ve landed on a more optimistic, productive take:

AI isn’t killing writing instruction; it’s exposing the underlying fragility that was already there. For too long, writing has been a performative act in the classroom, often formulaic and void of meaning. Tools like ChatGPT displace the ownership of effort in the writing process, furthering this disconnect even more.

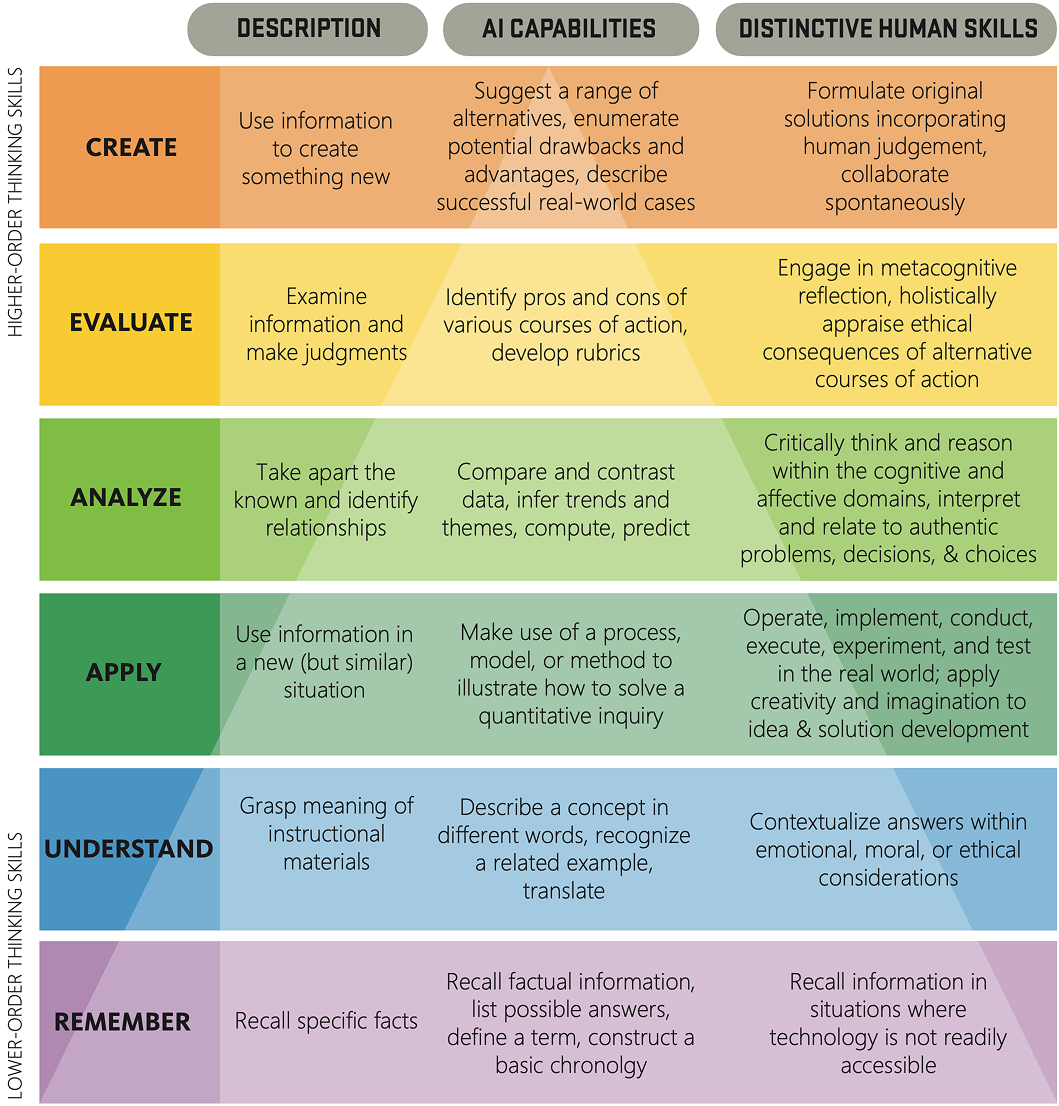

But without downplaying the herculean task ahead, if we teach students to use AI as a collaborative partner rather than a shortcut, we might finally begin to repair what’s long been broken in how we teach writing. Offloading the mechanical parts of writing can actually free students to think more deeply and engage in higher-order thinking, but only if they learn to use these tools with intention and discernment.

Writing skills have been in decline long before LLMs

Writing proficiency has been dismal in the last decade, well before ChatGPT made its debut. The National Assessment of Educational Progress’s (NAEP) comprehensive writing assessment in 2011 found that only 27% of students from grades four through twelve demonstrated proficiency in writing skills. While large-scale data on writing has been limited since, colleges are increasingly adding remedial composition classes for undergraduates who are ill-equipped for college-level writing.

A few reasons for the decline can be chalked up to:

Rigid structure and reliance on the five-paragraph essay: While easier to grade and scale, it has made writing feel formulaic at the expense of creativity and voice.

Writing instruction disconnected from the real world: Writing instruction overindexes on essays, rather than practical formats we engage with in real life e.g. email, newsletters, social media, YouTube videos.

Inauthentic audiences: Rather than conveying a message to a real audience, students submit their writing to a teacher for the sole purpose of assessment (not to be enjoyed or to learn something).

Not writing enough: Writing is often taught in isolated units and for high-stakes tasks rather than as a regular habit, limiting the ability to experiment with voice and develop the muscle needed to become a good writer.

Students often view writing as a means to an end, rather than a tool for thought. To get the grade they need. To get into college. It’s no wonder proficiency has declined and kids generally grow to dislike it.

ChatGPT exacerbated the “means to an end” mentality

For many students, ChatGPT supercharged the mindset that writing is a means to an end. The implications from the higher education study confirm this tradeoff: ChatGPT makes writing easier (reducing time and effort) with more creative outputs (number of ideas and variety of ideas), but decrease students’ enjoyment and creativity throughout the process. The use of AI led to a diminished sense of intellectual effort and accomplishment, especially among less sophisticated and experienced ChatGPT users.

ChatGPT’s ability to produce acceptable, and in some cases superior outputs leaves students with an even bigger dilemma. What is my role in this process and why am I writing this when AI can do it for me?

Why we should still care about teaching good writing

As Matt Bateman puts it in a recent talk on AI in the classroom, “writing is a power tool for thought.”

Formal schooling didn’t emerge to teach math or science, it was created to teach writing. From the scribal schools of ancient Mesopotamia to the civil service education of imperial China, writing was treated as a sacred and deeply human craft. Somewhere along the way, we lost that reverence.

Writing is hard, and so is teaching it. But the ability to write is central to the ability to think, to produce your own original thoughts and ideas. It may be prudent to offload certain writing tasks to AI, especially those that benefit from clarity over personal voice, but more than ever, authentic voice and experience will be critical to a society inundated by AI-generated content.

Teaching good writing, independent of teaching students how to use AI, is important because it develops their own thought. Thoughts become judgment, and judgment becomes authority—skills students need in order to use AI with sophistication.

AI as a creative partner

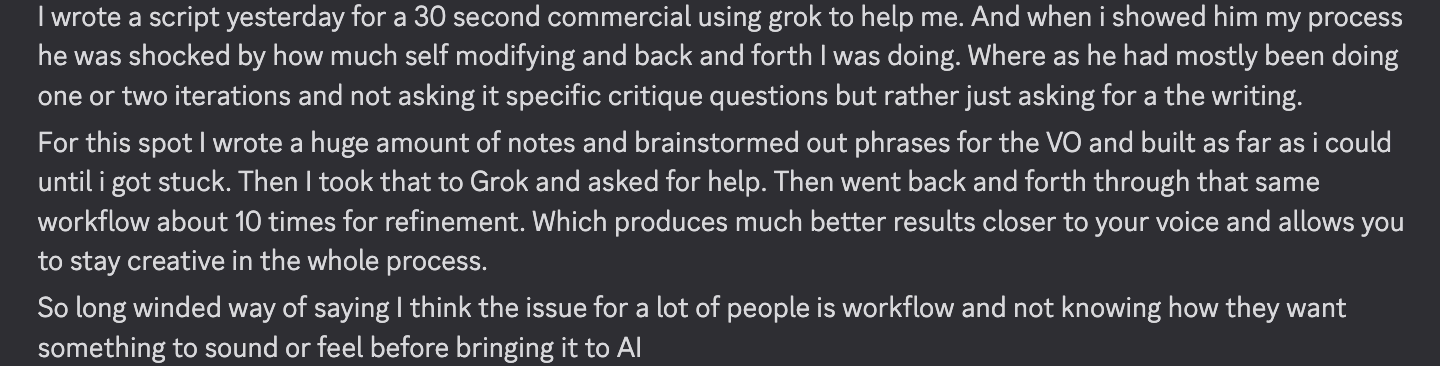

A close friend of mine, Kyle, is a seasoned video producer who’s been experimenting with GenAI in genuinely creative ways. With decades of experience producing creative videos, he doesn’t see AI as a threat to his work. Instead, he’s embracing it to explore ideas that would’ve once required far more time and money to bring to life. When I think of AI as a creative partner, Kyle comes to mind. He possesses a strong foundation in film, along with the creative intuition and judgment to engage with GenAI in a strategic, iterative process.

In an ideal world, this is how students approach writing with tools like ChatGPT at their disposal.

But obviously, that’s much easier said than done. Students are still early in their writing journey and don’t possess the same years of experience and maturity to intuitively engage with AI in such a way. They need a recipe of strong guidance on how to use AI critically and with discernment, where AI acts as a thought partner, not a substitute. This, coupled with better foundational writing instruction, and more opportunities to write in real-world contexts.

Some initial ideas on how to approach this:

Embrace, rather than ban AI. Instead of banning AI tools outright, schools should focus on thoughtful integration. Students are using these tools regardless, so it’s imperative they’re taught how to use it.

Model AI use openly and critically. Students need to see what thoughtful engagement with AI looks like. Teachers can demo how to prompt AI for feedback, then question its suggestions.

Give students structured opportunities to co-create with AI. Build assignments where students are encouraged to collaborate with AI e.g., ask it to play devil’s advocate, generate alternate endings, or offer edits that they can accept or reject.

Make the writing process visible through a changelog. Have students share not just the final draft, but how they got there, including how they used (or didn’t use) AI. This could look like submitting screenshots of AI chats, writing short reflections on what they changed, or walking through their revisions. The more students are asked to reflect on their process, the more they learn to own it.

Design writing tasks that are rooted in real perspective. Prompts that ask students to write about personal experiences or nuanced opinions are harder for AI to fake and easier for students to feel invested in.

Treat AI literacy like digital literacy. Understanding how tools like ChatGPT work, and where they pull information from should be part of the writing curriculum. Writing instruction should also include ethical considerations like data privacy and the difference between using AI to enhance thinking versus outsourcing it entirely.

Thoughtful use of AI in the classroom depends on teachers who understand these tools themselves. None of this will matter if teachers aren’t trained and supported first.

Regaining our footing with writing instruction

“This invention will produce forgetfulness in the minds of those who learn to use it, because they will not practice their memory. Their trust in writing, produced by external characters which are no part of themselves, will discourage the use of their own memory within them.” —Plato, Phaedrus (circa 370 BCE)

Plato’s warning about writing, spoken through Socrates in Phaedrus, feels eerily familiar in this moment. Where writing once provoked fears of intellectual decline, today’s generative tools stir a similar unease. If AI can generate ideas and language so swiftly, will students still come to value the slower, messier process of writing itself?

And yet, the written word did not erode human thought. It expanded it, not by replacing the mind, but by inviting it into new forms of expression. AI holds that same potential, if students are taught to approach it with intention and a sense of authorship. Shaping and challenging what these tools offer rather than being passive recipients.

To regain our footing in writing instruction is not to retreat from innovation, but to reclaim intention. It means creating space for students to develop discernment, so that what they create in partnership with AI still bears the mark of their own curiosity and judgment.

The technology will continue to evolve. The task is the same: to help students become capable thinkers.

References

Davies, W. V. (1987). Egyptian hieroglyphs. British Museum Press.

Elman, B. A. (2001). From philosophy to philology: Intellectual and social aspects of change in late Imperial China (2nd ed.). Harvard University Asia Center.

Marrou, H.-I. (1956). A history of education in antiquity (G. Lamb, Trans.). University of Wisconsin Press.

Mei, P., Brewis, D. N., Nwaiwu, F., Sumanathilaka, D., Alva-Manchego, F., & Demaree-Cotton, J. (2025). If ChatGPT can do it, where is my creativity? Generative AI boosts performance but diminishes experience in creative writing. Computers in Human Behavior: Artificial Humans, 4, 100140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2025.100140

Michalowski, P. (2004). Writing and literacy in early Mesopotamia. In S. D. Houston (Ed.), The first writing: Script invention as history and process (pp. 49–70). Cambridge University Press.

Oregon State University Ecampus. (n.d.). Bloom’s Taxonomy revisited [Infographic]. Oregon State University. https://ecampus.oregonstate.edu/faculty/artificial-intelligence-tools/blooms-taxonomy-revisited/

This is great! Make writing meaningful again! :)