Serious thinking has gone offline

IRL, reputation, and the rebirth of collective intelligence

Something is pulling people out of their screens again. In late 2025, Edge City ran a month-long popup village in Patagonia. Hundreds of builders, artists, and researchers lived and worked together, co-creating more than 700 unconferences and piloting a new residency program. A multi-day protocol sprint was held with the Ethereum Foundation. An AI pipeline to tackle Erdős math problems launched and succeeded. Attendees ran live experiments on consciousness and cultural currency. Even the kids were vibe coding.

Edge City functions as a crucible for high-curiosity people, but it isn’t an outlier. Across tech and culture, IRL gatherings, popup (and permanent) cities, and social-intellectual in-person events are proliferating, to the point that 2026 is already being dubbed the year of analog.

On the surface, the trend toward going offline seems to be an obvious one: social media is no longer social, doomscrolling is rotting our brains, and human interaction is cool again. But in my circles, “touch grass” has become career advice. People aren’t just leaving the internet to recover their attention. They’re doing it to get non-replicable inputs and pressure-test non-obvious outputs. Niche IRL subculture is where you stop performing taste and start producing it, in dialogue with weird people and radical ideas. The kind of conditions where scenius tends to emerge.

It’s no surprise IRL events have taken off amid the AI boom. The tools have levelled the playing field for what any one person can do, but AI-native nerds who’ve spent the most time with the models are all the more deliberate in how they use them. After enough exposure, the sycophancy becomes obvious, and so does the fear of outsourcing too much thinking and deskilling yourself into the permanent underclass.

I’ve even noticed this showing up at the extremes. Catching up recently with a former colleague who’s well regarded as a sharp engineer, I was surprised to learn he hardly uses AI at all, aside from the occasional Cursor aid. It didn’t sound like a principled stand so much as a way to keep certain muscles intact.

As AI collapses earned effort, it seems plausible we’re developing an existential fatigue around the primary modes of thought as famously described by Daniel Kahneman in Thinking, Fast and Slow, System 1—fast, instinctive—and System 2—slow, deliberative thought. While Kahneman provides a useful framework for individual cognition, there’s a third, dialogic mode we have been overlooking. Perhaps, more than the Great Unplugging, this is a new renaissance for collective intelligence.

Thinking alone

We probably use the word “intelligence” more now than ever in human history. Yet, it’s not obvious we’re getting any clearer about what it means.

Intelligence is often treated as an individual attribute. Something a person possesses, and performs through grades, IQ scores, degrees, and later through work. This framing, however, reflects a particular institutional moment rather than a timeless understanding of intelligence.

In the pre-modern world, thinking predated intelligence as a concept. Thought was understood as relational and dialogic, and was cultivated through participation in Socratic dialogue in the time of Plato, and later through Aristotelian notions of the polis, rhetoric, and apprenticeship. Dialogue was not merely a teaching tool, but a mechanism through which knowledge was approached and revealed between minds. This began to change in the 17th century with the Cartesian split, which redefined knowledge as what could survive radical isolation. With Descartes’ cogito, thinking was severed from culture and dialogue, and relocated inside the private, internal mind:

I think, therefore I am. - Discourse on the Method (1637)

Over time, we moved from thinking as an internal process to a systemic one. Industrialization and mass schooling required thinking to become legible and in turn, prioritized certain modes of thinking over others. In the early 20th century, IQ tests and scientific management emerged to make thinking measurable, comparable, and administrable at scale. Workplaces soon followed suit, organizing around operational efficiency rather than open-ended collaboration. The knowledge worker’s thinking became modular—broken into OKRs, KPIs, and performance reports. Modern work has individualized accountability while systematizing thought, leaving little room for genuine collective intelligence.

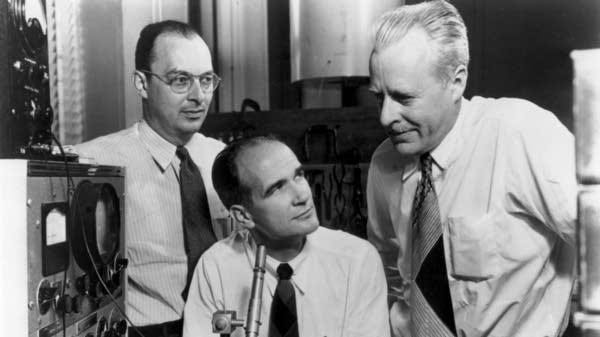

Bell Labs remains somewhat of a post-institutional anomaly for this reason. Mervin Kelly famously designed the corridors of Murray Hill to be incredibly long (some over 700 feet, the length of 2 football fields) to force scientists from different disciplines to bump into each other. The environment was designed for serendipitous encounters. Their open door policy and flattened hierarchy encouraged researchers to talk to each other. Importantly, Bell Labs was a space where slow productivity was encouraged, respecting the notion that the creative process could not be forced.

There are countless stories of innovation emerging from impromptu brainstorming sessions and lunchroom debates; casual spaces where dialogue emerged naturally. The invention of the transistor resulted from constant dialogue between theoretical physicists like John Bardeen and experimentalists like Walter Brattain. When AT&T’s patent lawyers were trying to understand what made certain individuals more successful, they stumbled on a common thread: workers with the most patents often shared meals with Harry Nyquist, a Bell Labs electrical engineer. Nyquist was exceptionally good at asking questions that “drew people out” and got them thinking. These collisions across thinkers and builders led to a staggering amount of innovation, including the transistor, the laser, the solar cell, and information theory. Bell Labs resisted legibility, yet has remained a clear outlier as a vanguard of innovation.

This kind of thinking doesn’t fit neatly into Kahneman’s System 1 or System 2 thinking. What Kahneman described as “fast” thinking is linked closely to sense perception and automatic functions; our “slow” mode of thinking is rational, reflective, and what is often associated with the term conscious thought. As functions of the brain, there’s a clear reason why we’d want to understand this phenomenon at an individual level. But these descriptions don’t capture the types of thinking that exist not in the single minds of isolation, but by the messier kind that occurs as socially engaged and interconnected beings.

This is what Michael Anton Dila has conceptualized as System 3 Thinking, a mode of thinking that is neither automatic nor effortful, as Kahneman describes of System 1 and System 2. Rather, it’s a mode of thinking that by definition “involves an engagement with multiplicity.” Put simply, System 3 thinking is collective thinking that happens when people think together. It’s differentiated in that it produces intelligence that doesn’t belong to any individual, and enables ideas that no single person in the room has conceived.

A further hypothesis is that System 3 is not only vital to engaging with complexity, it is itself irreducibly complex.

I first encountered this framework when attending Dila’s talk at a Toronto event this past fall. We discussed how conversation is a technology that enables thinking together, and how all conversation involves System 3 thinking. Not all conversation is created equal, though. Intimacy, immersion, and intention are essential. By his definition, face-to-face conversation has higher throughput than digital, and physical presence matters for full-spectrum thinking. There’s an embodied component to dialogue that is difficult to fully replicate online, even over a virtual call. Dila equates the exchange of System 3 to a form of play:

In this respect, the kind of conversation I am talking about here is game-like: both in the sense that there is no point in playing a game whose outcome is already known (that’s the very point of “playing,” after all) and in the sense that participating in a conversation, like playing a game, means being guided by and observing “rules,” but is something far greater than a series of rule-bound exchanges.

But we don’t think about conversation as a disciplined practice like we used to. Somewhere along the way we lost the forums to get past small talk. We lost the symposia, salon culture, and the coffeehouses. These were wrappers that made conversation a serious, ongoing practice; something you keep returning to even when it’s difficult, like going to the gym or practicing yoga. Rarely would we consider discussion to be a form of cognitive fitness, in the way we’ve made working out a legible form of physical fitness.

I think it’s time we do.

The duck who talks back

But then the question becomes, is dialoging with AI a form of System 3 thinking? We’re having conversations with LLMs all the time. ChatGPT users are sending about 2.5 billion prompts per day. Even the UI is meant to feel like a conversation. A very deliberate design choice was made about the interfaces of LLMs—from the response pacing to text streaming—to feel like you’re being responded to.

The response to Claude’s latest update Cowork has mostly been met with resounding praise, as the next wave becomes vibe coding personal software. Utility aside, there’s a nuanced perspective emerging that what’s efficient isn’t always best. And as the cyclical nature of society goes, we return to what works when faced with an existential crisis: you should be friction-maxxing.

Dialogue is a form of friction in a world where you can outsource most of your conversation to an LLM.

If System 3 arises when two or more participants experience emergent cognition that is not contained within any single participant, it’s not clear that LLMs currently activate this type of thinking. In this context, learning—of a durable, personal transformation kind—is asymmetric.

I’ve had conversations with people that leave me on a high for hours, the kind where you completely disassociate from your surroundings and lose track of time. The kind that fuels you with inspiration and creative energy to write a new piece, or obsessively go down niche rabbit holes. Despite how useful they are, I’ve personally never experienced this kind of embodied runner’s high from talking to ChatGPT.

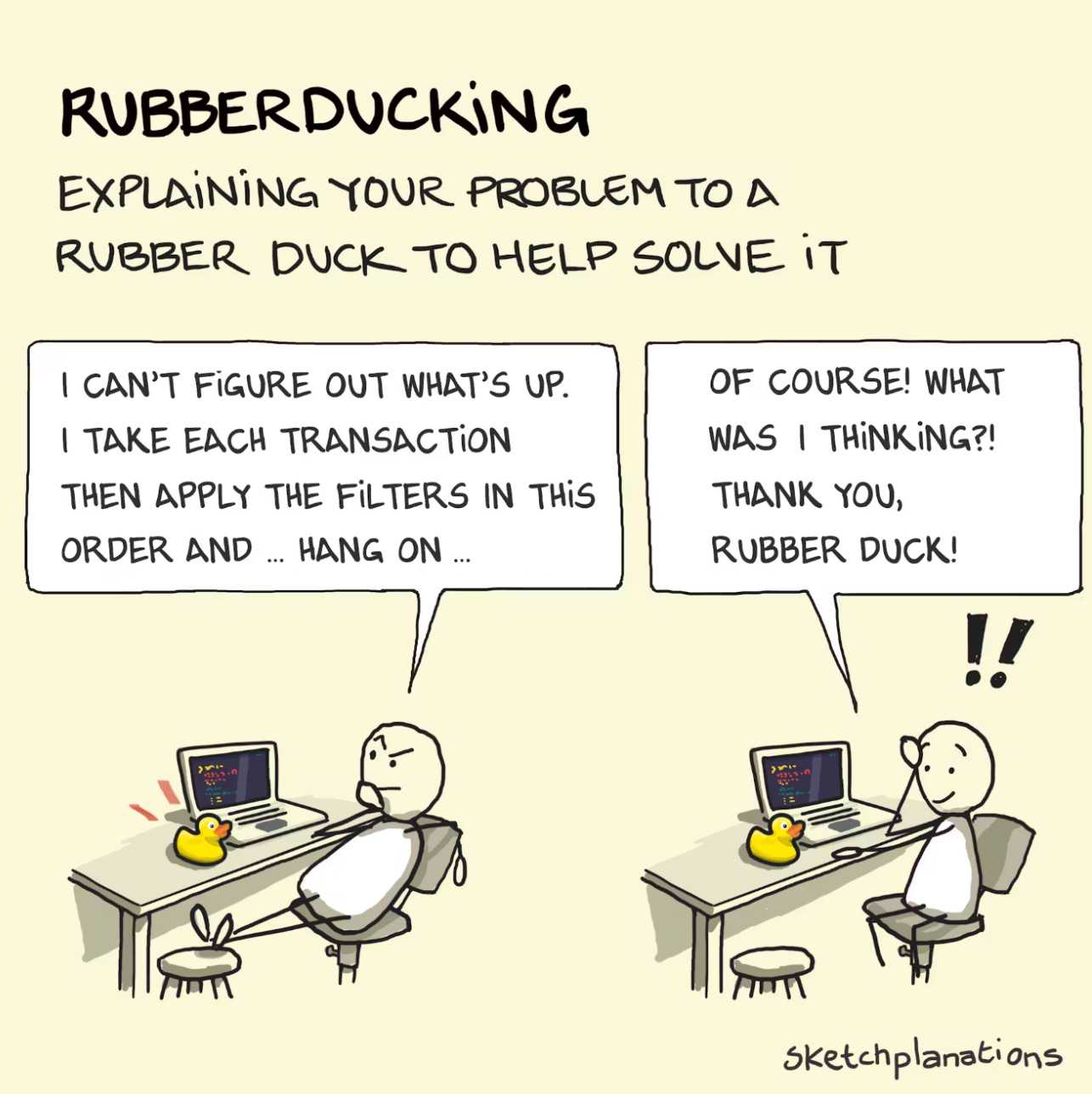

Conversing with LLMs may be more of a one-sided interaction, but it can be useful as a simulated version of System 3 thinking—a practice ground for thinking with others. Dialoging with an LLM can be a form of an extremely sophisticated “rubber ducking,” where you’re continuously explaining your thought-process in order to clarify your thinking. From this view, LLMs might not be entirely replicating System 3 thinking, but there’s clearly some simulated cognitive prosthesis at play and the potential to be a tool within this process.

Reputation

Another reason why outsourcing conversation to AI might not be wise is that human reputation is becoming the new currency. An anti-rule I’ve set for myself this year is that I won’t default to virtual meetings when an in-person option exists. While not always expedient, relationship building is far superior when you’re in the same room as the person you’re talking to.

And a big part of that relationship building is trust. As it becomes trivial to lie about your identity online and claim anything with zero stakes, people would literally rather fly across the country just to establish that who they’re talking to is legit.

Dead Internet is not just about false information. It's a lack of human connection.

The rise of IRL events, popup cities, and dinners is more curated and less transactional than it once was. It’s becoming less about how many people you know, and more about how well you are known to others. Not just anyone, but a small, high-signal group of people with whom you build bidirectional relationships and genuine human connection. Reputation becomes your capital.

Contrary to parasocial reputations—the perceptions people have of you who don’t actually know you—social reputations are built through repeated interactions over time. Your offline reputation is becoming incredibly valuable not only in terms of the groups and opportunities you gain access to, but the unique ideas you’re privy to. Unique because they couldn’t possibly exist without the meeting of minds in your specific milieu.

Judgment, taste, and authenticity get thrown out as the defensible skills in a post-AI world, but qualities like these don’t develop in a vacuum. They sharpen through differentiated inputs and feedback loops you get from sharing work with others. The Cultural Tutor has talked about his reluctance to read books from the last fifty years, primarily because that’s what everyone else is doing:

It’s a simple fact of life that if you consume, if you read what everyone else is reading, then the likelihood that you will write what they are writing, and worst of all, think what they are thinking, is increased.

Like differentiating the books you consume, participating in curated IRL subculture is a way to differentiate inputs. And like books that have stood the test of time, gaining the reputation of a classic, quality matters here too.

Convening IRL contrasts with knowledge-hoarding or building a second brain on Obsidian in one important way: you’re not just vibing with other people and ideas, you’re sharing your own outputs, ideas, lectures, demos, in a live, high-signal forum.

New social forms

Bell Labs didn’t happen because a bunch of nerds decided to get together for coffee.

It happened because Mervin Kelly was highly opinionated in how the organization was architected, from the space to social etiquette and values upheld.

Cultural infrastructure is a necessary part of the equation to a growing offline world.

Toby Shorin recently wrote a (really great) piece on social forms, which he defines as “the templates of social life” like dinner parties, book clubs, an all-hands meeting, or a first date. He argues that social forms predate institutions, the social forms that get solidified into law and power. In order to create the cultural conditions for new institutions, we need to radically experiment with social forms.

This is why I’m particularly bullish on groups of people taking these creative risks. Edge City and Edge Esmeralda are building curated multi-generational communities, where the majority of programming is bottom-up. Co-Founder Timour Kosters talks about how this design was intentional:

We approached everything with the mindset of emergence, meaning we created the container and intentionally left space for the community to shape the village themselves.

This becomes a breeding ground for emergent thinking.

Beyond the more extreme examples of social forms like Edge, I’m also noticing friends in my circles experiment with reading seminars, weekly “office hours” at a consistent location, attending/lecturing courses through community-run neighbourhood campuses, or creating third spaces in abandoned food courts.

When faced with an existential crisis, it’s society’s cyclical nature to return to what’s always worked. Human connection and dialogue are making a comeback, not for nostalgia’s sake, but as real, viable infrastructure.

If you made it this far, go touch some grass. Strike up a spontaneous conversation with someone you respect, and you might just land somewhere you didn’t expect. Talking is generative.

As always, thanks for taking the time to read and think with me here.

If you’re planning on attending Edge Esmeralda in Healdsburg this May, I’d love to connect there. Feel free to get in touch here or send me a DM.

-Sam

So good. This is the first piece I've read that adequately articulates what's really at stake. Particularly when it comes to AI dialogue, it's just simulacra.

great read!