Where greatness is banned

An education that fears heroes inevitably produces citizens who fear the future

The greatest danger to our future is apathy. ― Jane Goodall

Young people are 50% more likely to have a pessimistic outlook about the future compared to previous generations.

This is not simply teenage angst, but generation-wide disillusionment and defeatism about the future. This pessimism is not an overreaction to the state of the world, but the result of a flawed educational philosophy we have adopted.

Modern education has banned greatness.

The stories of great individuals were swapped for the relentless focus on systemic flaws and historical grievances. The unintended result is a generation taught that the world is a broken system to be critiqued, not a thing to be built.

But young people, more than ever, need something to aspire to. They need to internalize the belief that the world, while flawed, is still full of possibility.

The antidote is a curriculum of ambition, and that starts with a return to heroes.

If we want to raise a generation of ambitious builders and doers, rather than cynical spectators, we must give young people more exposure to the stories of high-agency individuals who made remarkable contributions to the world. This requires a fundamental rethink in how we approach education and even parenting.

the architecture of pessimism

Why has pessimism become so pervasive in young people?

Robert Pondiscio recently drew attention to the critical research on primal world beliefs, the fundamental, often subconscious, beliefs we hold about the world.

Primal world beliefs are the result of a decade-long study led by psychologist Jeremy Clifton that compiled and analyzed thousands of statements beginning with “The world is…” across media and popular culture, to identify three core, psychologically significant themes:

Is the world safe or dangerous?

Is it enticing or dull?

Is it alive or mechanistic?

These beliefs determine how you orient yourself in the world.

For example, if you believe the world is dangerous, this will manifest in hyper-vigilance and anxiousness. Conversely, if you believe the world is safe, you’re more likely to be trusting and calm. If you see the world as enticing, you’ll be curious and optimistic, but if you see it as dull, you’ll withdraw.

At the core of this study is what it counter-intuitively reveals: we don’t first experience the world and then inherit primal world beliefs. Instead, our primal world beliefs actively shape how we interpret our experiences.

It’s not a reaction to a bad world, but a lens that makes the world look bad.

modern education is a breeding ground for apathy

Doom scrolling. Bed rotting. Brain rot. Blackpilled. Chronically online.

Young generations are consuming messages of apathy and meaningless slop every day on social media. It’s practically unavoidable to be online and not feel a sense of dread as a passive spectator at the mercy of the algorithm.

But this malaise isn’t hardwired and it doesn’t have to be. Most kids spend 6 hours a day at school, a meaningful amount of time every day where we’re supposed to be enriching their lives and preparing them to become happy, well-adjusted adults. Instead, education like the media, has become riddled with the same doom-and-gloom messaging packaged under the guise of “critical thinking.”

You can see this shift across the curriculum. School reading lists now favor stories of pathologized teens over tales of perseverance. Climate change education often defaults to a narrative of "doom and gloom" catastrophe contributing to helplessness. Even civic education has been redesigned to teach students that the primary role of a citizen is not to build, but to confront crisis.

In one 2021 study, Clifton and Meindl found that 53 percent of parents preferred dangerous world beliefs for their children. They thought it would better prepare them for life. No similar data exist on teachers, but many features of contemporary education at least tacitly impart to children a view of the world as bad and broken — Robert Pondiscio

And to be clear, I do think it’s important to talk about nuance and not to understate the tragedies and realities of the past. But I fear we’ve overcorrected, meticulously critiquing the sins of the past while writing off achievements. In turn, young people have lost the sense of awe and optimism—what it means to be inspired by a truly remarkable human who achieves greatness in the face of difficult circumstances.

Our educational philosophy has become so risk-averse that it now operates on the unspoken principle: it is better to have no heroes at all than to admire an imperfect one.

If young people are not getting exposure to heroic, high-agency examples of greatness in the classroom or even at home, who are their role models? It’s no wonder most kids turn to YouTubers and influencers and that becoming a YouTuber or TikToker is a top career choice for Gen Alpha.

Before young people even have a chance to become ambitious, we’re telling them the world is a place that is unjust and to be feared. Their inputs become negative primals so it’s hardly surprising this is how they choose to respond to the world around them.

the antidote is a curriculum of ambition

A curriculum of ambition works by directly counteracting the negative primals that breed pessimism, and instead cultivating world beliefs of optimism. You cannot be what you cannot see. This is where heroes provide a powerful case study.

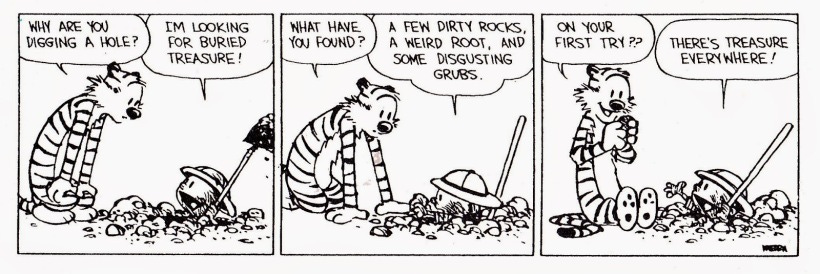

Presenting heroes as high-agency individuals who confronted immense challenges, not as flawless idols, provides students with a powerful antidote to the narrative of helplessness.

Heroic narratives are rarely stories of easy victory. They are stories of struggle, failure, and relentless effort. When kids witness this, they internalize that greatness is forged in grit, not granted by circumstance. These case studies lay the foundation for high-agency and provide the psychological capital needed to become daring and ambitious.

In a 2022 Psychological Science study, young girls playing a tough science game showed low persistence. But when researchers told them to simply pretend to be Marie Curie, their persistence nearly doubled. They adopted her agency.

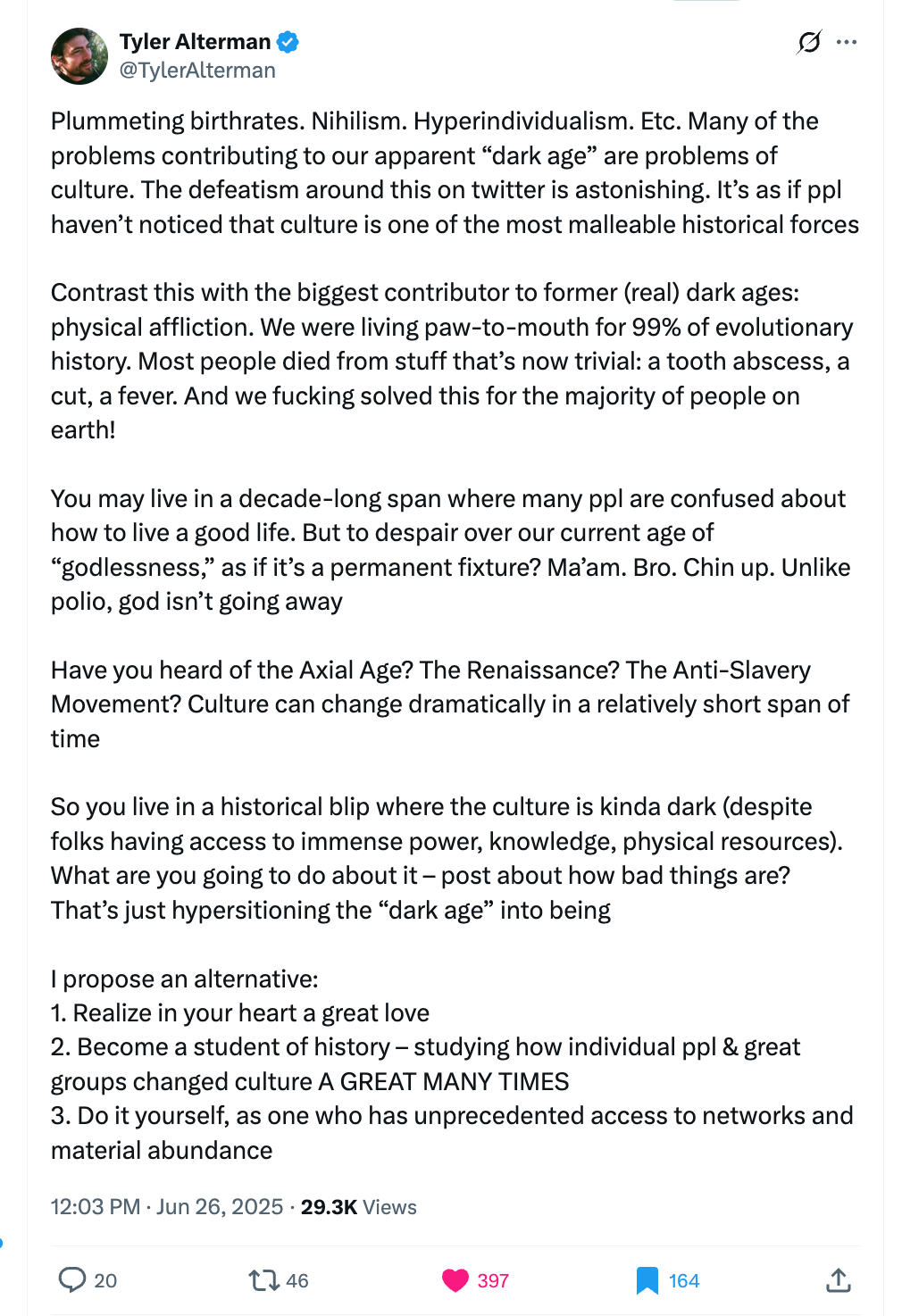

The stories of human achievement ground young people in the belief that individual action is meaningful and that striving for the remarkable is a valid and worthy pursuit. As Tyler Alterman noted in a recent viral tweet, the primary antidote to our modern ‘dark age’ of defeatism is to once again become students of how great individuals changed the world. This is how we move a generation from being cynical spectators to becoming the ambitious builders and doers the world desperately needs.

the architecture of optimism

I feel strongly about an education rooted in heroes because I’m the product of one. Growing up in a Montessori classroom, I was surrounded by evidence of human greatness and achievements.

One in particular that had a strong impact on my way of seeing the world was Jane Goodall. I have vivid memories of being absolutely mesmerized by her accomplishments after attending a science exhibit (it happened to be this massive 6,000 sq. ft. travelling exhibit that debuted in Sudbury, Ontario!). Because of the nature of Montessori, this interest I developed was encouraged and I spent following weeks obsessing over Jane Goodall’s life and work, propelling me into topics on conservation and the natural world. But more than that, I was in awe of this woman who had quite literally decided to pick up on a shoestring expedition to Gombe, Tanzania to study chimpanzees, with no degree or funding, and in doing so, reshaped our entire scientific worldview of animals. She did all of this in spite of plenty of adversity, skeptics, and the harsh realities of fieldwork.

Jane Goodall became a powerful, early model of high-agency for me. Her determination to pursue her dream, despite adverse societal and academic norms at the time, was a radical act of self-belief. And this, no doubt, played a role in nurturing my own understanding of what was possible.

Montessori’s philosophy is grounded in humanism and a fundamental optimism about people. Jane Goodall was one of many heroic examples of individuals that I was exposed to in my early years and I believe it contributed immensely to my sense of optimism and curiosity about the world.

This legacy of achievement is so powerful it recently inspired me to launch The Montessorians, the largest open-source dataset celebrating remarkable Montessori alumni.

"[Montessori] worried that we’ll fail to appreciate the inventions, achievements, and creations of civilization" — Matt Bateman.

This fundamental belief in human potential is the same principle now powering the resurgence of Classical education and modern models like Acton Academy.

a choice between cynicism and ambition

This, then, is the choice we face in our homes and our schools. We can continue to tell our children the world is a terrible place, or we can give them the stories and heroes they need to become the architects of a better future.

As for me, my own path was set long ago. It’s no accident that a girl raised in a world shaped by Maria Montessori would one day feel compelled to build a better education herself.

If this post resonated with you, consider sharing it with someone in your network who might also be thinking about these ideas.

As always, thanks for reading.

-Sam

P.S. — If you're curious about your own "primal world beliefs," the researchers have a great (and free) set of surveys you can take here.

Thank you for this awesome essay Sam! Having inspiring role models (both in your life and who you encounter through your education) can be so powerful. I hope we can do better to give young people examples of people doing heroic things (while keeping the nuance, as you mentioned). I think this point about the world being systems that we (you and me!) can build is so important, or else we're just stuck reacting to the whims of history.

Sam! Your work is exactly why I read substack. Amazing job!