Work is how we become human

Work-life balance is a lie. What Montessori taught me about true integration

Work-life balance is a lie we were all told before we even knew what a career was.

It hasn’t always been this way though. The concept of partitioning work and life is a relatively new phenomenon. Before the push for the 8-hour workday emerged as a response to the Industrial Revolution, working life was profoundly seasonal and embedded in the home and community. You didn’t “go to work”; the bread made, the fields tended, the cloth woven, all formed a single, integrated fabric of one’s life.

Work-life balance deceives us into thinking that work and life are opposing forces. In practice, you can never quite fully surrender to either. The internet has quarrelled over the work-life balance debate for the past decade. In tech and founder circles, most will at least agree it’s a flawed and outdated way of seeing how we work.

But the harm it inflicts is more insidious than we give it credit for. We lose something inherently valuable when we exist with this false dichotomy of work and life. We lose the opportunity to build a meaningful, wholly integrated life. The careful act of boundary setting will deny you the ability to reach for anything at all. Work simply becomes a mechanical act, as a sole means to an end. At an individual level this manifests as apathy. At a societal level, stunted progress.

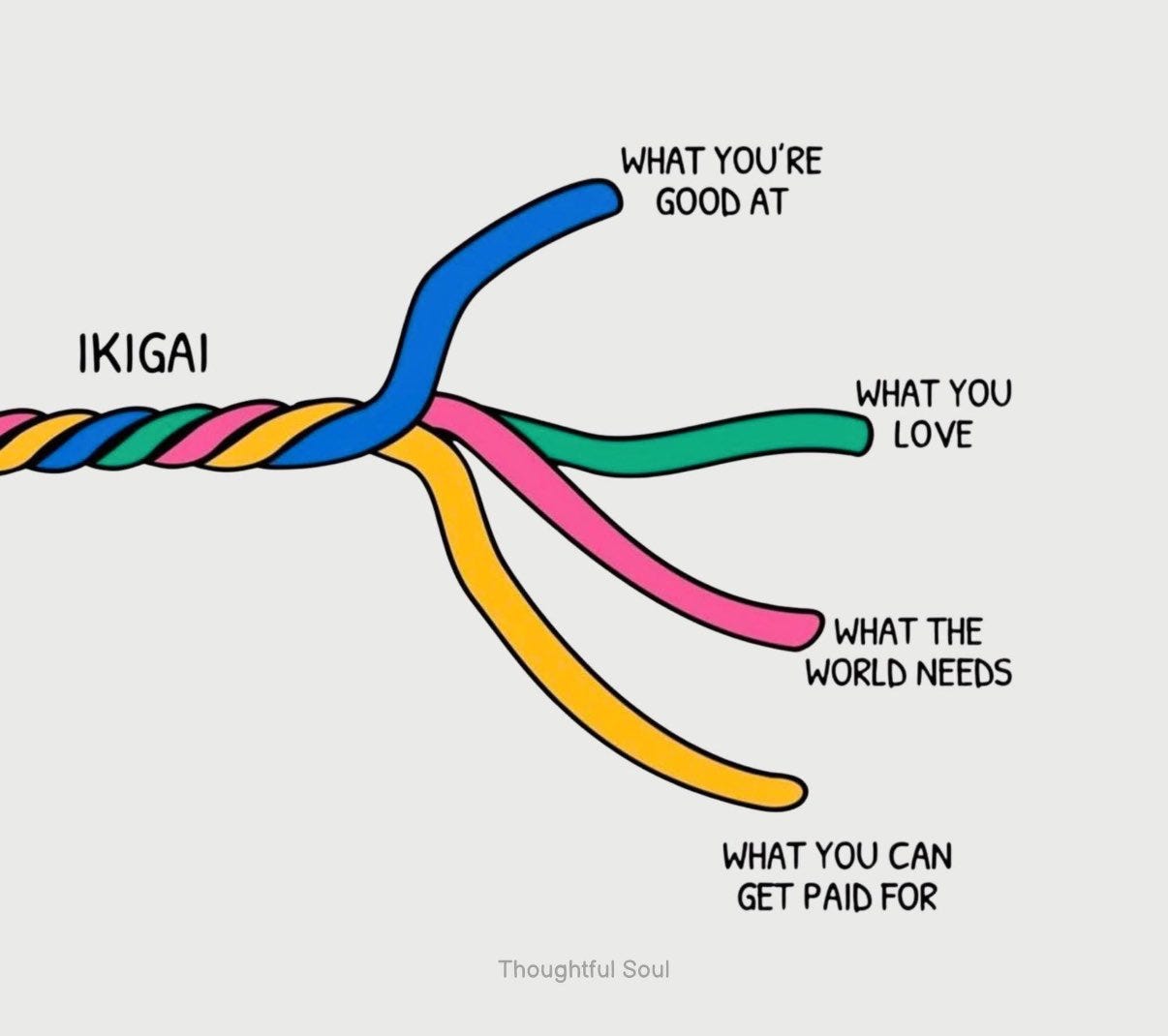

A healthier framework to live by is one of integration. Work-life integration corresponds with a deep intention behind the choices you make, and the agency you have in how you choose to spend your time. This may sound utopian to the average working adult. But that’s simply because our relationship to work is not something we develop the second we get our first job. It’s seeded far earlier, in an education system that trains us to see work as something to endure and play as the reward for getting through it.

In the age of autocomplete, we’re forced to confront a reality where industries undergo dramatic transformation and jobs disappear entirely. Montessori’s philosophy teaches us something important about what work is for and how it preserves our humanness.

Montessori’s philosophy on work

I’m convinced my relationship to work has always been positive because of how I was introduced to it at Montessori.

One of the many reasons why I’m Montessori-pilled is because of how it taught me to think about work. I was just four years old when I started at my Montessori school, and the concept of a work cycle was introduced to me. These daily work cycles consisted of three hours of uninterrupted work. And there was no kid-gloving what we were doing—it was very explicitly called work and treated with a similar seriousness. But this seriousness wasn’t a deterrent for enjoyment, nor contrasted with play as the desirable reward for effort. The sustained focus of independent work cycles and ability to choose what we worked on unlocked what I’d later learn was a flow state. And from that point onward, I’ve chased that feeling.

It occurred to me that most young people rarely experience this feeling once they enter school. On the basis of “engagement,” traditional schools train teachers to interrupt students every few minutes, sometimes as often as every four(!), and change activities before any deep focus can take root.

Montessori believed that work isn’t just something we do, it’s how we become. Montessori saw moral character as something built through deliberate, effortful work—an inner discipline that, when cultivated broadly, could raise the level of society as a whole. In The Secret of Childhood she writes:

It is certain that the child’s attitude towards work represents a vital instinct; for without work his personality cannot organize itself and deviates from the normal lines of its construction. Man builds himself through working… using his hands as the instruments of his ego, the organ of his individual mind and will. The child’s instinct confirms the fact that work is an inherent tendency in human nature; it is the characteristic instinct of the human race.

For Montessori, the significance of work goes beyond skill-building. It’s a child’s first experience of moral agency: choosing, persisting, correcting, and contributing. The classroom is not just preparing students for future jobs. It is preparing them to become the kind of people who can act with purpose in the world.

Work in a Montessori classroom is deeply personal and meaningful. It’s how a person continues their self-construction, not only in childhood but throughout adulthood. It’s not about choosing what’s easiest either; we’re naturally wired to choose work that is effortful, and worthy of our abilities. This chosen difficulty is what Montessori believes builds our character. In her view, work is not just economic activity—it’s the primary arena for moral development.

Montessori’s philosophy would reject the concept of work-life balance. Productivity hacking, multitasking, and work purely for external ends prevent us from building the moral development she identifies as critical to individual actualization and collective action.

Work-life integration*

A few months ago, when my husband, Karel Vuong, and I exited our last company, we had the opportunity to start from first principles: What do we care about? What do we want to build? What kind of lifestyle do we want to create for our future family?

Renaissance was born out of obsessive intention. We care about building better cultural infrastructure for agency and autonomy, and everything flows from this through line. Our relationships and the conversations we have. Our content diet. The values we orient ourselves to. They’re all harmonious to this central mission. We’ve realized it would be stifling to put up guardrails on when to talk about work and not, because it’s become far too core to who we are. And mostly because we genuinely enjoy it.

When there’s deep alignment between what you care about and what you’re working on, it’s like an infinite well that you can keep pulling from. We describe what we’re building as a modern family business, and naturally, choosing to work with your spouse means that your home, routines, and marriage become a kind of prepared environment for the work you’re trying to do together.

It occurred to me that what we’re doing is an adult expression of Montessori’s moral theory of work. And starting a company as a husband and wife duo, it turns out, is its own extreme version of work-life integration. It isn’t a model everyone can or should replicate, but for us, it has made the alignment between work and life unusually explicit.

But even before Karel and I made this transition, we had rejected any form of work-life balance. We were working all hours of the day in our previous company, where global employees and stakeholders often meant being on calls at 9am and 9pm. From the moment we woke up we were glued to our phones. There was a sense of urgency to always be on; we understood it was necessary and came with the territory of our work. This was likely some pathologized version of work-life integration, where work became our life but lacked deeper purpose. You see this faulty relationship to work manifest in hustle culture, toxic productivity, and trends like 996.

On its own, a period of working intensely isn’t pathological—I actually think most people should have at least one period in their life where they work unreasonably hard on something. And for many people, working to make money is meaningful in its own right. There is nothing trivial about wanting stability, or wanting to earn enough to change your circumstances, or wanting to support the people you love. Financial ambition is not at odds with meaningful work. It becomes a problem only when money becomes the entire frame, instead of one part of a larger arc of becoming.

Most people will have periods in their life where external ends take priority. Sometimes you take a job purely to pay rent, support family, or get a foot in the door. Early analyst roles, first sales jobs, shift work. These chapters are real, and sometimes necessary. The question is whether we treat them as the whole story (work as something to endure), or as part of a longer trajectory toward building skills, agency, and eventually alignment.

Work-life integration is often dismissed as a luxury. But alignment isn’t about wealth or status — it’s about coherence. A baker who takes pride in the quality of his sourdough may experience more harmony between work and life than the executive who spends half the day trying to hit inbox zero.

It’s understandable that most of the discourse around our relationship to work lives in the domain of adult life. Having experienced Montessori firsthand though, I’ve understood it to be a much more formative experience.

Our relationship to work is not something that magically unfolds when we leave college and start applying for our first real job. The problem lies in how we’re taught to think about work when we’re young.

Unlike Montessori, traditional school is a potent source of work-life misalignment. There are rare opportunities to choose your own work, let alone spend more than a few minutes on it without being interrupted. The moral outsourcing through external judgment via grades and teacher approval conditions young people to work for validation, rather than integrity of process. Traditional education hasn’t exactly been touted as the place where agency thrives, and that’s a generous assessment.

When your only exposure to work for years is transactional, resting solely on whether you pass or fail, it’s internalized as something external to yourself. You didn’t choose it. You didn’t connect to it. It doesn’t matter. Effort is merely a proxy for obedience.

The apathy we see in young adults today is downstream of education. When work becomes purely instrumental, we lose the part of work that shapes us. We lose the experiences that build judgment, discipline, and a sense of contribution. There are existing frameworks that can be applied at an individual level to help you cultivate a healthy relationship to work later in life. But ultimately, if we care about changing the cultural infrastructure at large, we need to address how young people are exposed to work in their early institutions.

While reading Slow Productivity recently, it struck me how much crossover Cal Newport’s book has with Montessori’s approach to work, specifically around the necessity of slowing down to accomplish meaningful work.

He talks about three specific ways that this slowing down occurs:

(1) Do fewer things; (2) Work at a natural pace; and (3) Obsess over quality

In an effort to evade pseudo-productivity, Newport proposes relentless pruning of tasks, arguing that in order to produce high-quality work, we must limit daily goals and focus on a few important things. He points out that we’ve inherited a false equivalent of industrial notions to productivity:

As I argued in the first part of this book, when knowledge work emerged as a major economic sector in the twentieth century, we reacted to the shock of all this newness by adapting hurried, industrial notions of productivity.

Working relentlessly to check off items on a list leaves no time to think, and leads inevitably to burnout and aimlessness. Work-life integration embraces the ebb and flow of living necessary to inspire original thought. When we consider the lives of extraordinary people, we see gaps of time, often years or decades before they have a breakthrough.

Newport’s framework is specifically aimed at knowledge workers and creatives, where measurable output is conceptual. It isn’t practically applicable for someone working in a role where output is linear, and has billable hours, like the trades. That said, these principles can be applied indirectly across all facets of work e.g. choosing not to take on too many projects to protect long-term physical health, building a reputation as the top 1% in a particular domain.

At a systems level, there’s promising next-gen education that acknowledges the importance of young people building a healthy relationship to work. Alongside the enduring movement of Montessori, new models like Alpha are guided by their central promise, “kids will love school” while being academically challenged and self-driven. Co-founder Joe Liemandt often says, “We want to build it so the kids want to go to school instead of going on vacation.” However this manifests, I’m optimistic that new and existing models are gaining mainstream attention as alternatives to traditional education.

Work is not autocomplete for life

Whether we view work as something to embrace or dread, there’s no denying the existential fear collectively felt about a world without jobs. The AI discourse has played on our fear of the unknown. If we consider work purely a means to an end, then a world of human work appears superfluous. But this grossly underestimates the value of work as a moral good, and vessel for becoming—or remaining—human.

Montessori would not frame this crisis as a loss of work, but rather a loss of meaning. If anything, she’d see this inflection point as the ultimate test of agency. A machine can autocomplete tasks, but only a human can choose a life. AI might replace jobs, tasks, or productivity, but it can’t replace human work. In this moment in time, we’re presented with an opportunity to be more intentional about the work we choose to do, and find better alignment with the kind of work that forces us off autopilot. AI can predict almost anything, except who we decide to become.

In the next few weeks, I’ll be revealing more about what we’re building at Renaissance. Personally excited to share more about the direction we’re taking and what we’ve been working on with all of you!

If this post resonated with you, consider sharing it with someone in your network who might also be thinking about these ideas.

As always, thanks for reading.

-Sam

Nice!